By Mary Klein, diocesan archivist

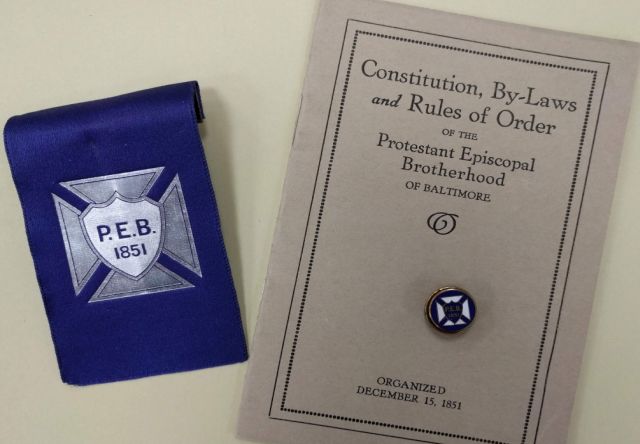

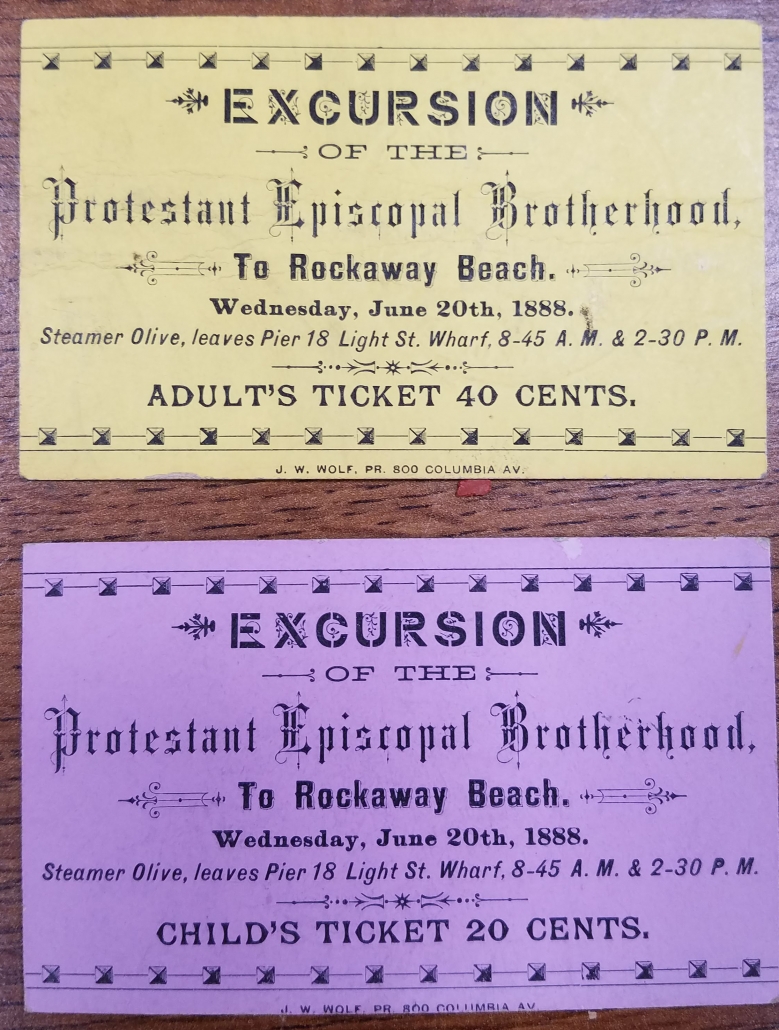

The Protestant Episcopal Brotherhood was “an organization of churchmen founded for benevolent purposes” in 1851. In the preamble it is stated that their purpose was to “associate ourselves for the purpose of mutual benefit in times of sickness and distress, for the promotion of Christian fellowship and love, and for the dispensation of temporal and spiritual aid and comfort to all who are in need of sympathy.” Those who were eligible included “every clergyman of the Church, a resident of the Diocese of Maryland, and every layman, baptized or confirmed, or a communicant in the Protestant Episcopal Church, if a resident of the Diocese of Maryland…” The dues were steep: three to five dollars to join, depending upon age, and two dollars every quarter. In return, a member who could not work received $5 dollars a week disability for the first 13 weeks, $3 per week for the next 13 weeks, and $2 per week for the remainder of his illness. (One man’s benefits went on for 179 weeks!) There was also a payment of $100 toward funeral expenses, as well as a $20 payment upon the death of a wife. A Widows’ and Orphans’ Fund also existed, as well as a Charity Fund.

In a day when unemployment insurance was unheard-of and unions were not prevalent in Maryland, a mutual benefit association which would provide some assistance while a man could not earn a living, was a God-send. Destitution could haunt a family quickly if the bread-winner were incapacitated; so the safety net provided by the Brotherhood, the vast majority of whom lived in Baltimore, probably spared many families the horrors of poverty.

The membership application form asked several interesting questions: “Are you temperate in all your habits?”, “Will you endeavor to increase the membership for the Brotherhood and promulgate its interests?”, “Are you able to earn a livelihood?”. The rector of the applicant’s parish had to be named and three Brothers had to recommend the applicant. There was also a medical examination required, a printed form appearing in about 1900. A physician examined the applicant and reported on his height, weight, heart and lungs. An interesting question was, “Are you ruptured, and if so, will you wear a truss?” That must have been a big problem, if it showed up on a medical exam form! The applicants were all men, at least 18 years of age, and looking at the height and weight figures is interesting to us a century later. The forms from 1903 until 1907 indicate that height ranged from 5’ 4 ½ “ to 5’ 11”, and the weight from 110 pounds (on a man 5’8”) to 156 pounds on a man 5’7”. Ages of the men applying ranged from 18-42, and most were shorter than today’s man and much lighter in weight, the average height being 5’8” and weight 134 pounds. Diets and work habits apparently make a huge difference in determining weight and height.

Occupations of applicants are also interesting to study. Of course there were clergy, as well as bookkeepers, students, salesmen and real estate brokers, but the vast majority seemed to clerks.

The prevalence of corner stores meant lots of clerks were needed. There was also a Supreme Court bailiff, a music teacher, a proofreader, a draughtsman, and a boilermaker. Machinist’s helpers, apprentices, telephone operators, attorneys, and stonecutters also applied; as did a car repairer, a confectioner, a post office clerk, a dentist, a stenographer, a paperhanger and a sexton. Merchants, bank clerks, laborers, as well as a moulder, a “general collector” and a glassmaker round out the occupation list. The list itself gives us a glimpse into the social structure of turn-of –the-century Baltimore, as well as the job market.

Receiving sick benefits didn’t happen just as a matter of course. A member on the Relief Committee paid the sick Brother a visit to verify that he was ill and deserved the payment. A physician also had to send a note to the Brotherhood stating that the member was under his care and was unable to perform the duties for the carrying out of his occupation. In about 1900 a standard form was available for the application for sick benefits, requiring the physician to determine if the illness or injury was “caused by intemperance or any immoral conduct.” Diagnoses may appear strange to modern ears. Nervous prostration, lumbago, sciatica, acute mental aberration, pleurisy, malaria and typhoid were all reported. Injuries included being fallen upon by a sleigh, sprained ankles, poisoning, broken ribs, mashed hands, dislocated hips, broken wrists, puncture wounds, and run-away horse accidents. Rheumatism and pneumonia were common, as were stomach troubles, tonsillitis, and bronchitis. “La grippe” was reported often; we know it today as the flu. One man was diagnosed with “locomotor ataxia” and nervous exhaustion and was later confined to a mental institution.

During the years 1891 to 1903, one Maryland clergyman received benefits often. Born in 1835, aging and apparently prone to accidents. He was 66 years old in 1901 when he filed a claim saying that he was prevented from performing his usual duties because he had been injured by a run-away horse. In 1902 he was injured again (this time the cause was not given), and in 1903 he was diagnosed with “printer’s arm”, whatever that might be. He also filed claims in 1891, 1892, 1894, and 1895.

Another clergyman seemed to have been plagued with nervous disorders, as well as other problems. Although he left the diocese in 1886, he continued to belong to the Brotherhood, pay his dues, and receive sick benefits. In 1892 he was diagnosed with “herpes zoster”, what we call shingles; in 1893 his sleigh fell on him, causing several weeks of disability, and in 1895 he was diagnosed with malaria. Advent and Christmas must have been overwhelming for him, because the doctor’s report filed on December 25, 1901 said that he had a breakdown caused by overwork and nervous prostration. This diagnosis was repeated in 1902, and he died December, 1902 at the age of 60.

Modern insurance possibilities made inroads into the Protestant Episcopal Brotherhood’s stance as the sole help of many disabled workers in the Diocese, and the Brotherhood dissolved in 1966. There were forty members remaining and each received $200.00 at the dissolution. The Brotherhood’s resources of over $10,000.00 were turned over to the Diocese, thus bringing to an end a century-old experiment in relief, disability insurance and fellowship.